On Christmas Eve, I received quite an unexpected surprise–an unsolicited invitation to become a “LinkedIn” connection with none other than Harry S. Truman. Holy cow! After all, it isn’t every day that I am honored to network with a former Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of the United States of America.

Now, I must admit that my decades of legal training caused me to raise some questions about this unexpected “request.”

For starters, while I am no history major, a quick check confirmed that President Harry S. Truman died in 1971, more than 30 years before LinkedIn was founded.

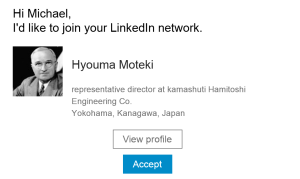

Despite my trepidation, I could not get over the invitation which reads as follows:

I know, I know – the name on the invitation is not Harry S. Truman. But the picture? The tie, the suit, the facial expression, the hair, the glasses, the background? Come on. A quick search on Google Images revealed that the man who purports to be “Hyouma Moteki” a “Representative Director” of a Japanese company called “Kamashuti Hamitoshi Engineering Co.” is none other than “Give ‘Em Hell Harry” Truman, our 33rd President.

Yes, it is the Christmas season. And I do so want to believe. But alas, logic leaves me with one of two choices. Either Harry Truman is still alive (at 131 years of age, he would be the oldest living person in the world), changed his identity, and secretly relocated to the island nation he once pummeled into submission with not one but two atomic bombs. Or, in the alternative, “Mr. Hyouma Moteki” of “Kamashuti Hamitoshi Engineering Co.” is a fraud.

Methinks the latter. In fact, there is no such entity.

But then why on earth would someone go through all of the trouble of creating a fictitious social media identity and then reach out to the likes of me? To answer this question, let me relay for you something that happened to yours truly a few months ago.

But before I tell you my social media (attempted) scam story, a little background is in order.

First, please recognize that I do not consider myself to be gullible. Quite the contrary, I am distrustful by nature. Been that way my whole life, as far as I can remember. Maybe it was my New York City upbringing in the 1970s. The first “card game” I ever played was a street con called “three card monte.” I was 12 years old with $20 of hard earned paper route money burning a hole in my pocket. A simple game – three cards. Two black, one red. The dealer “shuffles” the cards. Spot the red card and double your bet. I swore I spotted the red card. And when I lost (was taken), it felt as if someone had kicked me in the stomach. I later learned this was a scam. “Never again,” I swore.

Fast forward to the early 1990s, I used to receive a fairly regular email dosage of the “Nigerian Letter” scam. I am sure that most of you, at one point in your life or another, received some version of this missive. They were laughable.

You know the gist–some poor schmuck, maybe even a “Prince” or royal family member, usually from somewhere in Africa, finds themselves sitting on an obscene amount of cash. Except, for some long drawn out reason that makes no sense at all, they cannot seem to get the money out of the country without your help. In return for what sounds like doing next to nothing, you are promised literally millions of dollars. No risk.

Regardless of the details, the scam generally involves having the soon-to-be-millionaire victim forward some amount of real money to the scammers. Why would anyone do that, you might ask? Well, greed for one. The desire to believe, for another. And frankly some of the scammers can tell a very convincing story. The victims want to believe and view the payment of real money as a small token compared to the riches they are promised. So the victim transfers out good money to facilitate a transaction that never transpires. The scammer vanishes, along with the victim’s funds.

How Social Media Facilitates Fraudsters, Crooks and Scam Artists

How Social Media Facilitates Fraudsters, Crooks and Scam Artists

Fast forward further to 2015. What, you might ask, does the Nigerian Letter Scam have to do with social media? Plenty, I am afraid.

I focus on LinkedIn because it bills itself as “The world’s largest professional network” with a staggering 300 million members. Lawyers love social media, and they especially love LinkedIn. To be sure, according to one resource:

lawyers are increasingly acknowledging the importance of understanding–and using–social media. For some lawyers it’s because social is being used as evidence in their clients’ cases, for others it’s shaping up to be a great networking and business development tool, and some lawyers are using it for those purposes and more.

Regardless of the reasons, lawyers are participating on social media more often–and the most ABA’s annual legal technology survey offers further proof of this fact. The findings from the ABA’s 2014 Legal Technology Report indicate that lawyers are using social media tools more than ever before, with solo and small firm attorneys often leading the way, although large firm lawyers occasionally lead the pack.

LinkedIn is by far the most popular social network with lawyers. According to the ABA Report, 99% of individual lawyers from firms of 100 or more have a LinkedIn profile, followed by 97% of respondents from firms of 10-49 attorneys, 94% of respondents from firms of 2-9 attorneys, and 93% of solo respondents.

And, we are told by marketing experts that not only should lawyers be using LinkedIn but we would be really, really stupid if we didn’t. For example, in a recent article appropriately entitled, “3 reasons why lawyers should love LinkedIn,” the author advises (admonishes?) lawyers to “love” LinkedIn because:

- It is easier for lawyers to “get found” online if they have a LinkedIn profile;

- The platform is “quick and easy” to use, like, share, demonstrate your expertise, and “stay in front of your connections”; and

- LinkedIn is “self updating” so that if your contacts change jobs or update their profile, you instantly get that updated information.

For lawyers who, like myself, don’t trust anybody, I must say that I too have fallen for LinkedIn. I have found the platform to provide an invaluable tool for quickly vetting opposing counsel, potential witnesses, clients, and prospects. In fact, if a professional I am investigating does not have a LinkedIn profile, the absence arouses my suspicion. It makes me wonder what are they hiding.

Guess Who Else “Loves” LinkedIn?

Guess Who Else “Loves” LinkedIn?

It sounds like the set up for another bad lawyer joke:

Q. What do you call millions of lawyers all connected on the same social media platform?

For the crooks, hucksters, scam artists and fraudsters of the world, the answer may be: “An excellent start.”

Here is how I almost got scammed by a new LinkedIn “connection.” I can ethically tell you this because: (a) it is a true story; and (b) there is no client confidentiality when the purported “client” is not a bona fide client and the communications with the lawyer are a mere pretense to defraud the lawyer. Plus I hope you will learn from this.

Once upon a time, about three months ago, I was invited to connect with someone who purported to be a Japanese businessman. His name was Ryoji Yoshida.

I checked out his LinkedIn profile. He had a number of connections, including some people I knew. He also purported to work for a company that I could verify, a Japanese publishing concern. He had a profile picture and background information too, which appeared legitimate (or, to be more precise, the information was not so obviously illegitimate, like my new friend Harry Truman). So I clicked “Yes” and voila, I made a new LinkedIn connection.

That is when the fun began

The LinkedIn Scam

A short time after we became social media pals, Mr. “Yoshida” sent me an “InMessage.” For those of you who are not on LinkedIn, an “InMessage” is essentially a private email message that a LinkedIn member can send to another member who is one of their connections. This is a feature I myself have used before, and so nothing jumped out at me as being unusual about the email, at least for purposes of an introduction.

Mr. Yoshida advised me that he had an IP licensing dispute with a publishing company near Baltimore. My office, it just so happens, is in Baltimore. He said he contacted me because he could see from LinkedIn that I was an IP attorney in Baltimore, and he wanted to know if I could represent his company in litigation against the Maryland-based licensee. My interest was piqued.

We began conversing online through my work email address. This is not unusual as I often make initial contacts and conduct conflict checks via email communications. He provided me with conflict check information and seemed to know the drill. His company checked out as a real entity having a real brick and mortar facility in Tokyo. And the adverse party also was a real company located just outside of Baltimore. Both were in the publishing business, just as Mr. Yoshida said.

Having cleared the conflicts, the putative “client” provided me with a copy of the licensing agreement, at my request.

I examined the agreement. It seemed real–at least there were words on paper; the words made sense; it had the look and feel of an IP license agreement; it was executed by representatives of the Maryland company and the Japanese company. And, very conveniently, it included a liquidated damages clause, which certainly helped for purposes of valuing the litigation.

I told “Mr. Yoshida” we would be willing to take on the engagement, but since he was a new client from a foreign country wanting to pursue U.S. litigation in federal district court, we would require a sizable advance payment. I explained how expensive litigation could be and provided information about the process. I drafted a rock solid engagement agreement, which included the advanced payment provision. Within a day, the agreement was returned, fully executed, no questions asked.

That was my first clue something was wrong. That was too easy, I thought.

The second clue something was wrong was the client’s email address–or rather, the lack of a bona fide corporate email address. This really caught my eye. No legitimate business person uses “Gmail” for highly sensitive legal matters. Something smelled.

I sent the purported “client” instructions for wiring me the advanced payment, and I told him that all future communications had to be through a corporate email account. He quickly responded to me something about his corporate email server being down–which was both plausible and, of course, completely unverifiable. And he promised to send me the retainer that day.

The third clue that caused me to question the veracity of this “client” was the time of his emails to me. His emails were being sent to me in the middle of the night Tokyo time. One email came at 2 AM local (Japan) time on a Sunday morning. If he really was in Japan, then that didn’t make any sense at all.

While I did not trust this guy, I could not get my head around the fraud. Where was it? He was sending me money as an advance, not the other way around. If the check was no good, then we would not enter our appearance. I could not see the angle. It was like the three card monte game of my yourth; I watched the shuffle, I knew exactly which card was red. There was no way I could get screwed.

Or so I thought.

Double Whopper With Fries

Just a couple of days after executing my engagement letter, on a Saturday morning at around 8 AM (or 10 PM on Saturday evening Tokyo time), my very excited “client” sent me an email. Evidently, the thought of litigating against me was enough to bring the defendant to its knees, or so I was told. I cannot do justice to the email so I recount it in full. Needless to say, the giant Whopper attempted fraud finally revealed itself:

Dear Mr. McCabe,

We are delighted to inform you that we received a message from our debtor accounting department, they have issued a partial payment of $480,000.00 owed to our company to avoid litigation after we brought to their notice our aim of seeking legal action. But as a matter of precaution, we remain unwavering in this potential legal matter because they have made such promises hitherto. The balance will be paid within couple of weeks.

They were pledging to make the payment which we are insisting must be through an attorney because they have made such pledge before, we will need your assistance throughout the process, we have informed them that we can only accept part payment on the ground that its made payable to an attorney.

You will have your retainer fee deducted from this sum and this will give us a good note to start off as agreed by my board of directors, we have given them 5 to 10 business days if the payment is not received, we will go ahead with the legal action.

Yours Sincerely,

Ryoji Yoshida

So there it was–the red card was finally revealed!

So there it was–the red card was finally revealed!

For doing essentially nothing, I was going to get a check for nearly half a million dollars. For my hour or two of “work,” I would collect a six figure “retainer.” Good money if you can earn it. Of course, the catch was that I would be required to deposit someone else’s money (the purported defendant’s) in my law firm’s trust account. Why a legitimate client would “need” to have the money go through an attorney made no sense at all. And from that, I would then have to cut “my client” a check (on good funds) made payable to “my client.”

You might ask, why not just wait until the “check” cleared before sending the erstwhile “client” his cut? Many banks will tell their clients that a check is “cleared” and the funds are available immediately or shortly after the funds are deposited. Yet with a counterfeit check, it can take a bank weeks, or even months, for the fraud to be discovered. Once the financial institution learns the underlying check is a fake, the “deposit” is reversed. If any portion of the fake funds were expended, the bank will demand its money back in full.

I may have been born at night, but it wasn’t last night. And that is exactly what I told Mr. Yoshida. I also congratulated him on his attempted scam; in my words: “Congratulations, you have come a long way since the Nigerian letter scam.”

The next day, “Mr. Yoshida” wrote back. He did not deny his fraud. He simply told me that I was “very funny” and to “please return the payment once received, you are not ready to assist us.” This email too came at 3 AM local (Tokyo) time. Mr. Yoshida is obviously the hardest working man in Tokyo.

Our emails must have crossed because the very next day, I received a check payable to my law firm in the sum of $480,000. The check looked and felt like the real deal. While I am no expert, the check smelled. For example, it purported to be drawn on a Quebec branch of “The Bank of Nova Scotia.” Yet, the putative defendant that allegedly issued the check is a one-office operation incorporated and having its only place of business in Maryland. Why in the world would a Maryland publishing entity with no ties to Canada do its banking in Canada? And in a community surrounded by literally dozens of national U.S. banks, why would this tiny publishing company be writing its checks from an account in Quebec with “The Bank of Nova Scotia.”

A quick phone call to the defendant company confirmed what I already knew. In fact, the company was a one woman shop that distributed publications on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. No dealings in Japan. No banking in Canada. No IP agreement. No check paid to any Japanese company. The person who allegedly signed the “license agreement” on behalf of the purported defendant company? Non-existent. It was all part of the Big Whopper.

Scammed Lawyers Run the Risk Of Professional Discipline

Scammed Lawyers Run the Risk Of Professional Discipline

According to a recent formal opinion published by the New York City Bar, “Internet-based scams targeting lawyers are not new and appear to be on the rise.” The opinion explains:

Since 2009, email scams have swindled lawyers out of an estimated $70 million. These scams are often highly sophisticated, involving parties that appear to be representing legitimate international corporations and using high-quality counterfeit checks that can take a bank weeks to discover. One experienced ring obtained $29 million over a two-year period from seventy lawyers in the United States and Canada. Once an attorney falls victim to a scam, his problems have just begun. Banks have sued attorneys for lost funds caused by counterfeit checks, and some malpractice insurers have refused to indemnify affected lawyers. See e.g., Lombardi, Walsh, Wakeman, Harrison, Amodeo & Davenport, P.C. v. American Guarantee and Liab. Ins. Co., 924 N.Y.S.2d 201 (3d Dep’t 2011)(coverage litigation between insurer and attorney, arising from settlement of bank’s lawsuit against attorney as a result of an overdraft caused by a counterfeit check); O’Brien & Wolf, L.L.P. v. Liberty Ins. Underwriters Inc., No. 11-cv-3748, 2012 WL 3156802 (D. Minn. Aug. 3, 2012) (holding that insurance company was required to cover losses from attorney trust account due to counterfeit check scheme); Attorneys Liab. Protection Soc., Inc. v. Whittington Law Assocs., PLLC, 961 F.Supp.2d 367 (D. N.H. 2013) (denying insurance coverage for losses due to “Nigerian check scam”). On top of that, a law firm that suspects or knows that it is a victim of an Internet scam faces serious questions about its ethical obligations.

To make matters worse, a scammed lawyer can be disciplined for violating his or her duties to other clients of the lawyer’s firm.

“For example, if an attorney’s trust account holds funds from multiple clients, then any funds that are transferred from the trust account to the email sender most likely belong to other clients of the firm. This would place the firm in violation of Rule 1.15(a), which imposes a fiduciary duty upon the attorney to preserve client funds. The loss of those client funds triggers other ethical obligations, including a duty to immediately notify all affected clients. See Rule 1.4(a)(1)(iii) (lawyer must “promptly inform the client of . . . material developments in the matter”).

In addition to suffering the reputational damage and financial losses that may come with falling victim to a scam, a lawyer who falls victim to a scam may be disciplined for violating the ethical duty of competence. According to some authorities, because “depositing a counterfeit check into a firm’s trust account can negatively impact an attorney’s other current clients whose funds are in the same account, an attorney who fails to exercise reasonable diligence to identify and avoid an Internet scam may violate Rule 1.1.”

In addition to suffering the reputational damage and financial losses that may come with falling victim to a scam, a lawyer who falls victim to a scam may be disciplined for violating the ethical duty of competence. According to some authorities, because “depositing a counterfeit check into a firm’s trust account can negatively impact an attorney’s other current clients whose funds are in the same account, an attorney who fails to exercise reasonable diligence to identify and avoid an Internet scam may violate Rule 1.1.”

For those who are subject to the disciplinary jurisdiction of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), falling victim to an internet scam can lead to an ethics investigation by the Office of Enrollment and Discipline (OED). If the OED determines the scammed practitioner violated any of the USPTO’s ethics rules, the scammed practitioner could run the risk of a license suspension or other forms of discipline.

Be Careful Out There

I sent “Mr. Yoshida” an email advising him that his “check” was fake. I asked for his home address so I could return his check. Surprisingly, no response has been forthcoming.

I have decided to keep the check as a memento of my brush with evil, a terrible accident avoided, and to serve as a reminder for myself that I am not as smart as I like to think.

This incident also serves as a reminder of the ethical risks of social media. LinkedIn is a great tool, for sure. But lurking among the legitimate lawyers and potential clients are predators. We are their prey.

Three card monte, welcome to LinkedIn. Would you like to join my network?

The clearest “tells” of these scams are (1) email from supposed huge corporations that come from aol, yahoo, or gmail type accounts, and (2) basic grammatical errors, often at 6th grade level.

Attorneys at my firm receive emails initiating this kind of scam almost monthly. The first time, I did respond (even though it certainly smelled bad that the sender was using a gmail account) but I figured what have I got to lose. When I saw the “contract” I knew it was a scam. It was so poorly written, none of it made sense (although it was obviously lifted at some level from a real IP agreement) and was basically meaningless. The signature also didn’t match the name of the signer (I assume they change the names frequently but not the signature). I never responded.

I also never accept a Linkedin invitation from someone I don’t know. But the sad part is, i can see how some attorneys may fall for this and ruin their practice.